Mr. Jude Ocampo, DFDL Deputy Head, Regional Tax Practice Group, wrote this article on Thai-American Business Magazine. The article examines one of the significant trade-offs involved in setting tax policy: economic growth vs. economic inclusion. It looks into how the balance between direct and indirect taxes plays a role in the development of the Thai economy.

Thailand is one of the greatest developmental success stories in recent history. In 2011, the World Bank acknowledged Thailand’s rapid economic rise as it upgraded the country from a middle-income economy classification to an upper-middle income economy. A senior World Bank Economist stated then: “The upgrade is in recognition of Thai-land’s economic achievements in the past decade in which GNI per capita has almost doubled, while poverty has been significantly reduced. The country has been prudent in macroeconomic management with a strong fiscal stance and low public debts and inflation. Thailand has a friendly business environment and has been successful in attracting foreign direct investments and achieving greater diversification in manufacturing production, both in terms of higher value-added production and expansion into new emerging export markets.” In simpler terms, the upgrade recognized that Thailand’s impressive economic performance in the first decade of this century was characterized not only by an increase in the size of the country’s economic production but also by a distribution of this growth in a way that led to a reduced incidence of poverty. This is significant because as recent global events and academic research have amply demonstrated, non-inclusive economic growth is unsustainable – economically, politically and socially. Indeed, the elevation of a sizable chunk of a population out of poverty and to the middle-class is both (i) a validation of the effectiveness of a country’s economic policies and (ii) an indication of the sustainability of economic growth. Tax policy is a vital element in a country’s overall economic policy. Governments must, of course, raise revenue for the expansion and upkeep of physical infrastructure, the financing of the bureaucracy and the implementation of social and poverty alleviation programs. Note however that tax policy involves more than just tweaking tax rates to raise sufficient revenue to support public programs. Just as important is the manner by which such revenue is raised.

DIRECT TAXES, INDIRECT TAXES AND PROGRESSIVITY

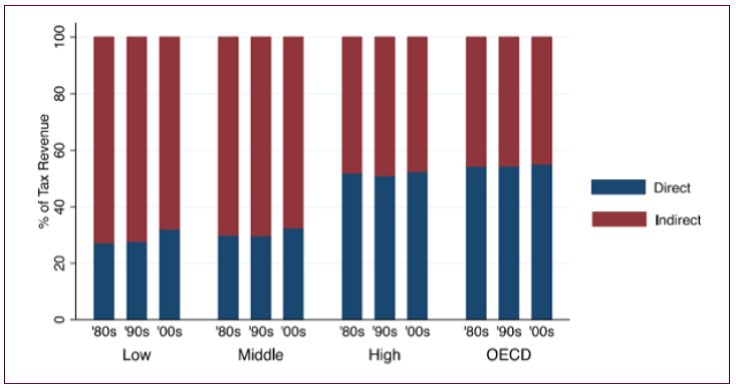

Taxation’s indirect distributive effect is widely recognized (Figure 1). For example, a majority of income taxes are collected from a small subset of corporations or a relatively small portion the overall population, yet they are directed to fund public programs and infrastructure that can be used by or which redound to the benefit of all members of society.

Figure 1: Global Trends: low and middle income states rely more heavily on indirect Taxes than Direct Taxes. In Structures, Economic Growth and Development; Kyle McNabb and Philippe LeMay-Boucher (2014)

What is less recognized is that the imposition of different types of taxes also has immediate distributive effects. Depending on the type and manner of collection of these taxes, the effect could either sup-port an equitable sharing of the burden (progressive taxation) or impose heavier burdens on economically disadvantaged taxpayers than on more well-off sections of society (regressive taxation). Direct taxes such as personal and corporate income taxes typically require higher-income persons or entities to pay a larger fraction of their income to the state. The Thai personal income tax sys-tem is an example of this – the effective tax rate increases as the level of income increases (Figure 2).Indirect taxes such as consumption taxes impose the same level of taxes on all affected taxpayers. With the value added tax (“VAT”), for example, a middle-class family and an upper-class family buying the same basket of goods would pay the same amount of VAT. However the VAT paid by the middle-class family would constitute a higher fraction of its total in-come compared to its better off neighbor. To make the VAT system more equitable, states (especially developing economies) exempt basic commodities from VAT. This policy is grounded on the assumption that lower-income taxpayers spend most of their financial resources on these VAT-exempt goods and are therefore insulated from much of the burden imposed by the VAT system. Thailand’s VAT rules apply this policy through the exemption of the sale of certain agricultural products, certain animals or animal by-products, fertilizers, fishmeal’s & animal feeds and educational services. Note however that such exemptions, while reducing the burden of low-income earners, do not promote progressive taxation, since high-income taxpayers also enjoy the VAT exemptions.

To read the full article, please click here to download the pdf file.

To download the TAB Volume 5/2014 – Domestic Consumption and Growth, please click here.